From tagging on subway trains as a young rebel in the 1970s, Futura has reinvented himself a million times over and evolved as an artist to pioneer an abstract style of graffiti and bring street art into galleries. Not one to be pigeonholed into specific genres, he’s even ventured into fashion, designing military-style streetwear under his label, Futura Laboratories, and collaborated with brands like Nike, Hennessy and Levi's. For a time, he also went on tour with punk legends The Clash, live-painted during their concerts, and spit a few verses on one of their records. At 63 years old, he’s far from slowing down, making his return to Singapore for his first solo exhibition in Southeast Asia, Constellation. Just before a screening of his documentary (in conjunction with his exhibition) at The Projector, we sat down with the street art icon, and challenged him to create five sketches on the spot (based on five words) while speaking to us.

Futura, the Godfather of Street Art, is Not Done Evolving

It all starts with a name. Call it art or self-expression, the act of tagging a surface in public with your signature is how most graffiti artists get their start, announcing their presence to the world in big, bold letters. In a single scrawl, you turn from an odd-looking kid by the nerdy name of Leonard McGurr into a new persona that is now part of an underground army of street rebels and counterculture renegades. For Futura (then Futura 2000), this alias, so much of which is tied to the graffiti community, provided a remedy to his identity crisis when he discovered that he was adopted at 15—the same time he first picked up an aerosol can.

“My signature is my base identity. It’s how I got started in this whole experience. As far as identity goes, and the origins of who I am as a person, it begins with the graffiti culture I’m part of, and the signature or tag with the name I chose, as an alias,” he shares.

One moment he’s a young kid from New York with a black mother and a white father, and the next, he’s a lost sheep with no clues about where he came from. “I’m an alien,” he quips. “The other kids who were cut like me, black mother and white father, didn’t look like me. Their hair wasn’t like mine. There wasn’t much going on when I was 10 or 12, so there was a lot of time to look around and think. I was always in constant, question-mark mode.” Despite having his suspicions early on, when the truth finally unfolded, young Leonard went through a “depressing” time.

Solace came in the form of embracing his individuality as well as the realisation that “there are f**kin’ kids in Africa, Asia, South America, right down the block who’re also ‘bastard kids’. So what? Turn it around and just become something.” That was one of the first epiphanies the artist experienced that changed the trajectory of his life at 15.

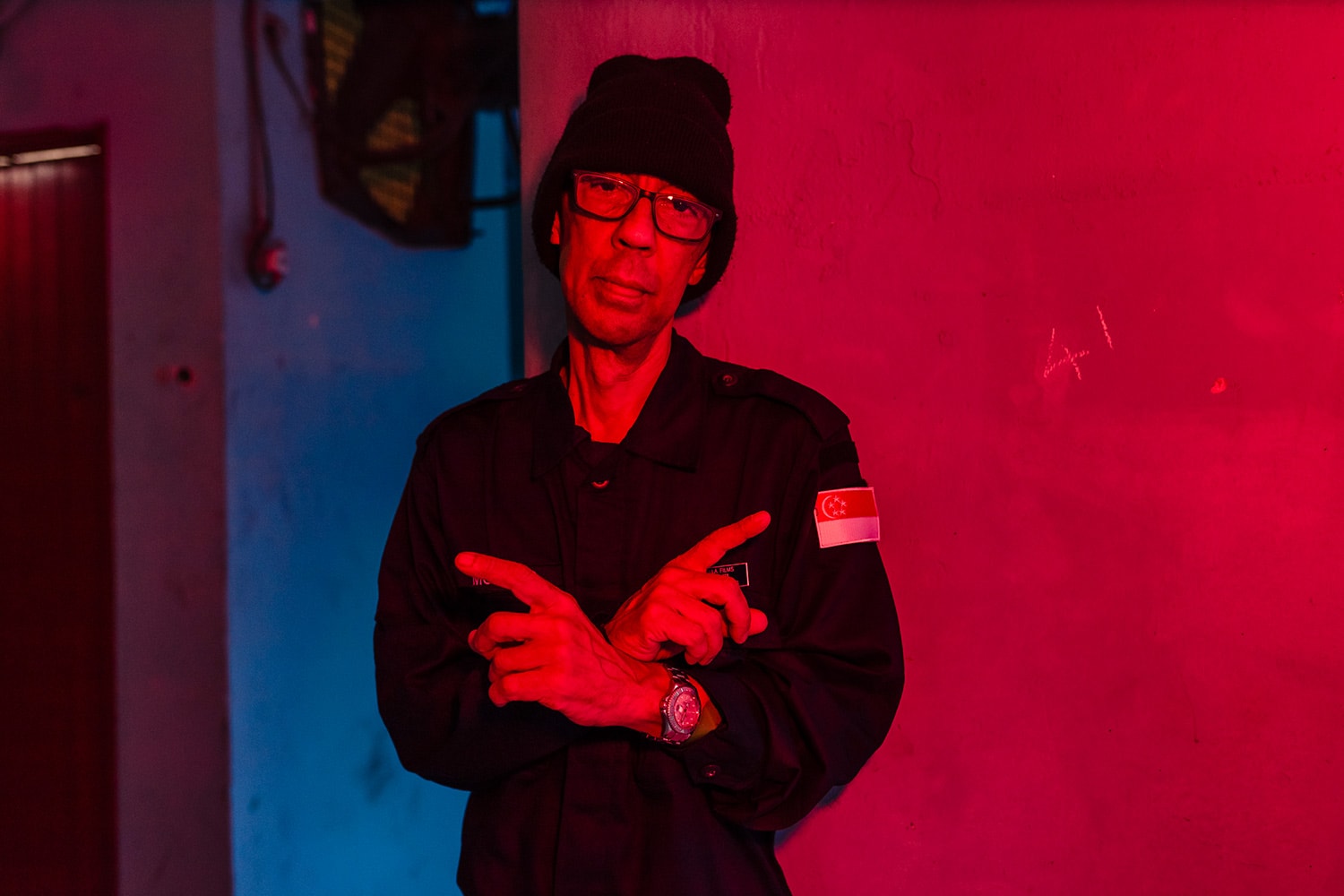

As I sit and chat with the godfather of graffiti at the rooftop carpark of Golden Mile Tower, the word, evolution, comes up repeatedly in my head. After all, this is the man who turned a tacky logo from a bottle of floor wax into an iconic symbol (the small yet mighty atom) that has defined much of his work. Even now, his mere presence is capable of turning a dingy old carpark into the edgiest interview space. The ground is rough and unpolished. Discarded boards and furniture are strewn to the side. The paint on the walls has faded and peeled off. It's gritty and unglamorous, like an abandoned building. Yet, the view from the fifth floor is also undeniably breath-taking. On any other day, I wouldn’t have given this location a second thought. But with Futura in the building, it suddenly transforms into a New York ghetto of sorts. That unadorned wooden door in the corner, which looks like it will lead you off the ledge, now seems like a thing of unorthodox beauty.

It’s about a month before the launch of his newest collaboration with Virgil Abloh, founder of Off-White and current menswear artistic director of Louis Vuitton, and a few hours before the debut screening of his documentary at The Projector. The film, presented and produced by local contemporary art gallery The Culture Story and street artist Jahan Loh, comes in conjunction with Futura’s inaugural solo exhibition, Constellation, in Southeast Asia. He's also in town to officially re-launch his streetwear brand Futura Laboratories at Dover Street Market, its exclusive global retail partner, after an eight-year hiatus. At 63 years old, the OG of OGs is still making art and pushing boundaries. You may think his prime years, touring with The Clash, pioneering a form of deconstructed graffiti, and bringing street art into high fashion, are over. But he’s just getting started.

Needless to say, after 48 years, Futura has grown up. He’s still stirring things up, but not in the way that he used to. “I had my moment rubbing up against punk culture. I feel like it’s an anti-establishment movement, where they’re kind of in rebellion against whatever or whoever they want to be in rebellion against. It’s not sustainable, just like with the hippie culture. All these individuals grow up. They mature. Even myself,” he opines.

“It’s like you’re 20, and the next minute you’re 40. What are you doing with your life then? Are you still a punk? Are you still wearing leather with spiked hair? I’m wearing some kind of punky type of bondage pants, but now it’s just fashion. [The punk culture] is way more niche than ever now. It’s a retro thing where people want to live in a kind of past. I don’t discredit it, but I feel that we have to move on. It’s about evolution. We can always respect those things and reflect on those cool genres, but let’s move on.”

Four decades ago, the street artist might’ve been one of those “random kids expressing their urban angst” just because it was de rigueur. From the outside, it looks like an act of rebellion, but if you’re simply copying what’s cool to fit in, you’re just participating in a different form of conformity. What makes Futura the legend that he is, is that he’s constantly moving forward and breaking the mould.

His attitude towards graffiti has inadvertently changed over the years as well. “I would argue that graffiti as its most crude base elements are just mindless tags with names and whatever—no style, no thought behind presenting something that maybe looked interesting,” he asserts. “I’m not ignorant to all of what it is because I can see my rebellious side, but I also see society’s anti-graffiti side. Now that I’m on the good side of it all, I get it. I don’t wanna see graffiti on nice shit. I don’t ever wanna see people defacing walls the way you see in Italy, like kids tagging on 400-year-old buildings. Man... Even when we were stupid kids in New York City writing on walls, we respected stuff.”

“Until 1980, we were all pretty much underground in that system we had. When we surfaced, we started calling ourselves graffiti artists. It’s weird. Just a title or a name defines who you are. Now, I don’t wanna be defined by anybody. I’m a unique person and I don’t wanna be categorised. It’s an insult to my intelligence and my originality.” It is this categorisation and pigeonholing of his identity that leads to what some may call selling out, as if an underground graffiti artist isn’t allowed to leave his nest and expand his creative palate with mainstream designers.

More than a street artist, fashion designer, graphic designer and graffiti pioneer, Futura is a family man who believes art and life are almost synonymous. “You create art, you create life. And if you create life, what kind of life are you going to create?” he asks.

“If anything’s happened from 1982 till today, it’s like I’ve done what I’ve done, and I try to contribute and do my thing, but I’ve also seen a lot, and even have two amazing children, who are 28 and 34. That’s the real reality of my life. I somehow managed to do both. That makes me feel very proud because it’s hard to do that. It’s hard to have a career that’s as amazing, maybe, as mine, and have that other part, family, that a lot of people envy. There’s a lot of cool artists that are successful, but what about the other part? That responsibility never dies. I wanna see people make the commitment for the long haul. Then, I’ll respect you and say, ‘My guy, f**k yeah, let’s take care of life and business.’”

Coming full circle now not just in his life (both personally and professionally), but also with his return to Singapore (his first visit was in 1977 as a young navy sailor on an aircraft carrier named Constellation), the offbeat doyen is aware of his status and influence, but doesn’t let it define his next steps. While there’s always pressure to outdo himself and do justice to the community at large, the priority is still to stay true to himself.

“I don’t want to be a one-hit wonder… I wanna evolve, and I see some growth in what I’m doing. [But] I don’t wanna disappoint myself first, because it’s all about me looking at myself in the mirror and just being truthful. There are times in my life when I was totally being full of shit, just in denial. I got all that sorted… Now, I’m at a place in my life where I don’t need anything, from anyone, and everything I’m getting I’m just so f**kin’ grateful for.”

Identity

“For me, I don’t know my biological family, so it leaves me open to a lot of imagination about where I come from. My daughter told me to take a DNA test and find out who my father is. I do a DNA test 50 years later, and find out we’re Turkish on my father’s side, but I still don’t know who he is or what he is. I know nothing about the actual backstory.”

Punk

“I think a lot of things has got to do with punk, although punk is not my culture. I feel it comes from Europe and London and that movement of the mid-70s into the early 80s with The Sex Pistols and The Clash whom I worked with in the early 80s.”

Erosion

“I saw more graffiti in Bali in 24 hours than I’d seen in Singapore in my last two visits spanning three weeks. In any other part of the world, I would see random kids expressing their urban angst and all this inner rebellion against society, and it’s not just them expressing, ‘Hey, I exist. This is me.’ It has to be somewhat seemingly tolerated to allow it to continue. The way you stop any virus is to cut it off right away. You don’t let it infect the system.”

Pressure

“Pressure’s more relatable to real-time… it’s like you’ve got a real job and you’re under a deadline, or you’re in the sporting realm and you know you’ve got a big match tonight and there’s pressure. I think for me the pressure’s pretty much whatever I perceive it to be. Right now, I’m kind of just doing my own thing and I guess I’m just waiting for people to get with me.”

Afterlife

“I’m not very religious in general, although I love the call to prayer. It’s kind of the coolest religious thing out there. I’m going to be reincarnated. I don’t think you get reincarnated until you’re like an ant, or a tree. I think you come back as another human being somewhere. I think that energy kind of gets sucked up… like, how can you die? It just seems too precious and valuable.”