Janice Koh is ready for me. She’s fitted in a full-length pantsuit from Stolen that cuts deeply at the back to reveal sinewy muscles and a faint bikini tan. Her hair coils lightly around a sharp chin while her lips, painted deep red, curls in a wry smile. Others might find white a difficult colour to don from top to toe, but Janice carries her outfit with confidence, making her appear taller than her 161cm frame. The same poise comes across when she speaks. Save for a furrowed brow, Janice embodies a stillness that magnifies her presence. Her eyes betray a quick mind as she navigates questions with skill—I feel her anticipating my sentences as if she had already prepared a script in advance. It is perhaps a characteristic that is second nature to her, after almost two decades of media attention. Performance for the veteran, however, is no longer limited to the screen and stage after being propelled into a new sphere of public scrutiny as an arts Nominated Member of Parliament in 2012. “It takes a lot of courage to just stand by your beliefs when you’re under so much pressure to conform,” she reflects. Being laid bare to national criticism was also a different test from the demands of juggling parliamentary duties alongside professional and family duties. The merciless public lens inspects even the minutiae of everyday life—and having each decision magnified was scary for the self-professed perfectionist. Failure was never kindly looked upon since her childhood. It has taken 15 years of Ashtanga yoga practice to start embracing failure as a necessary step for breakthroughs to happen, and this switch in perspective is especially pertinent now due to the unpredictable demands of being a mother. Although she lacks certainty in that role vis-à-vis her role as an actress, Janice acknowledges the challenges she faces with a candid humility, and has a deep self-awareness that she is still learning about herself every day.

A Candid Conversation with Janice Koh

XIANGYUN LIM: What are you currently reading?

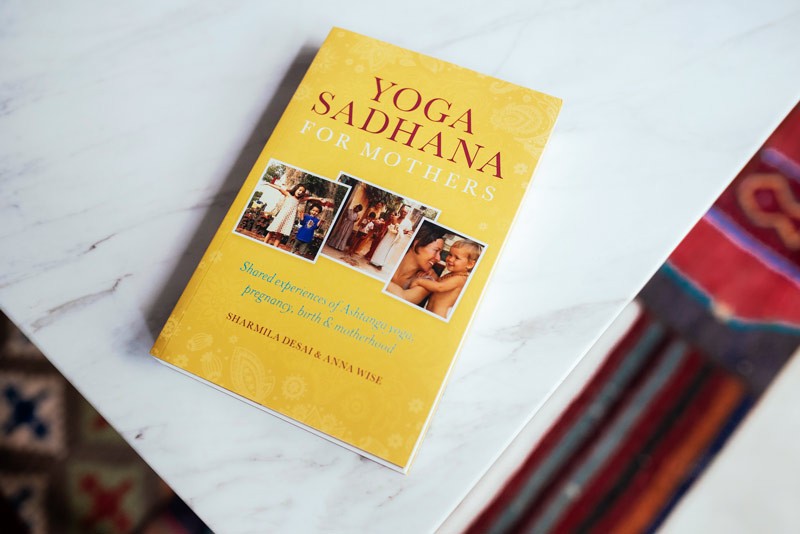

JANICE KOH: It is a book about yoga for mothers that a friend gifted, but that isn't what I usually read. I like Murakami and The Wind-up Bird Chronicle is amazing. Other books I return to are Jeanette Winterson’s Why be Normal When You Can Be Happy and classics like The Great Gatsby… I also occasionally read Singaporean poetry—it’s easier.

XIANGYUN: Sometimes I find that poetry takes more effort.

JANICE: It doesn’t need a huge commitment of time. Ever since having children, my bandwidth for reading novels have shortened incredibly. Social media is also very distracting. It’s like the new magazine. I have to literally put my phone away in order to finish a book.

XIANGYUN: You have always been quite vocal about your love for reading. Is that something you actively instil in your children?

JANICE: I firmly believe that if you teach a kid to read from a very young age, half your job is done. Once they can read independently, they’ll always look towards books for answers, knowledge and experience. My kids were surrounded by books since they were born, and I make sure they read as widely and diversely as possible. Max, my elder son, is a voracious reader, and he is probably more up-to-date on current affairs than me. For someone his age, it’s the best reminder that the world is a much bigger one—beyond his school and this house.

XIANGYUN: I was chatting with him and heard that he wrote a letter to the editor of The Straits Times.

JANICE: He was really upset when they cut the comics section. I told him: “Why don’t you tell the editor instead of telling me?” He did, but they never published it.

XIANGYUN: Did you ask him to try again?

JANICE: No. I saw it only as an exercise to show him that he can make his voice heard. You’ll never get anything if you don’t try.

XIANGYUN: Besides reading, do Max and Lucas go for classes outside of school?

JANICE: Both of them play soccer while Lucas takes art and piano classes. He’s also learning Japanese because he has a Japanese friend and loves the cuisine—he’s younger but shows real commitment and excitement for his classes. They don’t go for any tuition except for Mandarin. We let them pursue the things they want.

I hate the idea of a high-stakes test like PSLE because kids are no longer learning when it’s only about acing an exam.

XIANGYUN: Our education system doesn’t seem to allow our younger generation to explore the things they like.

JANICE: There’s not enough time. We’re so exams-driven that there’s a shadow education industry just for that boost and the extra 5% in results. I hate the idea of a high-stakes test like PSLE because kids are no longer learning when it’s only about acing an exam. The focus on academic performance also means that parents use whatever time is left after school to better their grades. I’m not surprised there is a pressure to start a family here.

XIANGYUN: What do you think should be the focus of education then?

JANICE: I believe in equipping a young child with a curiosity about the world, how to be creative about ideas and execute them, how to make friends at the playground, and the social skills required to work together as a team. Our education system is built such that these critical skills are only demanded after years of academic performance focus. By the time they reach tertiary education, it’s too late to flick the switch backwards.

XIANGYUN: So what you mean is that our education system leads to a cessation of critical thinking as well as less family time.

JANICE: What can we do? I may disagree with it very much but this is the system in which we exist. Let’s be real here. Not every school is a good one. Although there are tweaks being made to improve things, I feel that we’re not boldly facing the core issues of how we’re developing the younger generation. I wish for a curriculum that incorporates all aspects of education—and that includes music, sports and the arts. It may mean longer school days but once the kids come home, it’s all quality time with family and friends, not homework. There won’t be a need for parents to send them for more enrichment classes.

XIANGYUN: How do you feel towards Max taking his PSLE this year?

JANICE: I think it’s a choice whether to stress myself over it. It’s our own expectations to handle. Once you manage to detach yourself, you’ll see PSLE as just another exam. I don’t think I’m detached—my husband is. He believes that the kids will go to a school they deserve based on their own drive. Their work ethic matters more to me—nothing comes without hard work. I can live with average results if they put in their best effort.

XIANGYUN: Do you remember facing academic pressure as a student?

JANICE: Society was much more demographically and economically equal then, which meant less pressure to perform. Nowadays, those with privileged backgrounds continue to benefit from the advantages our system has for them, while those with similar capabilities with the lack of resources and parental support will find themselves falling behind very quickly.

XIANGYUN: Was it difficult for you to pursue a path in theatre?

JANICE: I grew up in a very working-class family. Both my parents only have O-Level certifications and there was zero exposure to the arts at home. It was my love for reading and literature that led me to theatre when I was 17, and that changed my life. My parents did get worried when I expressed desire to pursue drama in university because my mum had wanted me to try law.

XIANGYUN: How did that turn out?

JANICE: The interviewers for the law programme asked: “So Janice, why do you want to become a lawyer?” And I admitted that I didn't. I wanted to be an actor and I couldn’t lie—I knew exactly what I wanted.

XIANGYUN: Did the rest of your family respond in a similar way?

JANICE: I’ll still get asked at if I “zhuo hee” (做戲; putting on a show in Hokkien) by relatives at Chinese New Year gatherings every year [laughs]. There are no ill feelings because I understand that it’s a much less trodden path in Singapore. I’m so happy doing it that I don’t care.

XIANGYUN: Did you have financial concerns?

JANICE: I was very aware of the uncertainty surrounding this path and chose not to take up a huge bank loan. I had really wanted to pursue my degree overseas but there was no way my parents could have funded an annual cost of at least S$100,000. There weren’t many scholarships or sponsorships available for the arts industry then, and I eventually chose the BA programme at National University of Singapore. But I did a Masters in Theatre Administration in London that was supported by PSC.

XIANGYUN: Was there a reason why you wanted to go overseas?

JANICE: The local BA programme had a theoretical base—it was a branch of the general English department, but I knew I needed practical training on stage. So I created my own training programme by doing workshops and working at small black box shows almost every day.

XIANGYUN: How about working overseas?

JANICE: I made a pragmatic decision to stay in Singapore because the possibility of finding work in places like New York would be much smaller. It wasn’t an inclusive and diverse theatre landscape—there wasn’t blind casting and Asians mostly got minor roles. I knew, however, that the arts scene in Singapore was nascent and growing. And I wanted to be a working actor, not someone waiting on tables for a big break.

It’s not easy to be an artist in such an expensive city like Singapore, especially if you want to make work that’s impactful and groundbreaking.

XIANGYUN: It’s clear that you gave considerable thought to your choices.

JANICE: Sometimes when I look back at that period of time… I think I would’ve done it differently. I would’ve gone for an overseas degree—perhaps apply for overseas financial aid or find work there while studying. I would have tried to be braver.

XIANGYUN: Why do you use the word “brave”?

JANICE: Because I just didn’t have the courage to take a financial risk. Young people nowadays are more courageous. There’re even actors who have successfully crowdfunded their own degree! I’ll tell people now to give it a shot—you’re not going to do it at 35, with kids and a mortgage. Your 20s is a wonderful capsule of time with less commitment and a window of opportunity to take risks.

XIANGYUN: What do you think it takes?

JANICE: It takes a lot of hunger. It’s not easy to be an artist in such an expensive city like Singapore, especially if you want to make work that’s impactful and groundbreaking. It’s hard but I think it just takes a lot of guts and desire. Those who stick with it… just can’t imagine doing anything else.

XIANGYUN: And they’re willing to compromise on other things, like financial stability, to fulfil this hunger.

JANICE: Yes, because it’s not just about “making art”. It’s the need to speak, which is a sort of hunger that can't be denied. Even if you’re a late bloomer, the need will express itself later in life.

XIANGYUN: This can be a lonely path if you don’t find others who understand what you’re trying to do.

JANICE: [pauses] It is an interesting field. Those who choose to pursue any form of art can connect with like-minded people instantaneously because it takes so much to choose this path. There are so few out there that you hold on to each other for community and support. My beacons are those who are a good 10 years older than I am, like Lim Yu-Beng, Tan Kheng Hua, Ong Keng Sen, and Ivan Heng—they show me that it’s possible to build a life around art.

I don’t think Singapore places enough emphasis on the role of art in reflecting who we are—and that includes our flaws and strengths.

XIANGYUN: Do you think art betters the world?

JANICE: I think it betters society. An artist always creates for an audience, translating feelings into ideas that others can identify with. Their art builds empathy by saying: “I’ve felt this way—have you?” It’s not a one-dimensional process—it doesn’t just show our common humanity, but also our differences, conflicts, and the ugly side of society. Work that provokes debate and makes people angry and think, helps us move forward as a society. I don’t think Singapore places enough emphasis on the role of art in reflecting who we are—and that includes our flaws and strengths.

XIANGYUN: The ROI is a lot more intangible in this industry.

JANICE: Yet these intangibles are what keep us going. I sit on a few boards of theatre companies, and although we have to talk about the number of audience members and so on, the satisfaction ultimately comes from how much people were moved and touched.

XIANGYUN: How can this impact lead to something more lasting—like change?

JANICE: Change is not measurable. Art can only reflect the zeitgeist—the pulse of society at that time. But the change comes from us. It’s an ephemeral process in which you can’t pin down particular points in time where change occurs.

XIANGYUN: Only certain triggers.

JANICE: Yes, and it’s a huge success if art does that.

XIANGYUN: Have you met anyone who managed to suppress his or her connection or desire for art?

JANICE: All the time. But anything can be justified, there’s no right or wrong path. Only decisions. You can choose a career where your ROI is more tangible, and a life that’s more stable... and that’s what you live with.

XIANGYUN: Do you try to convince them?

JANICE: I think that was my role in Parliament—to be an advocate.

XIANGYUN: How did being an Arts NMP help you further your cause?

JANICE: Being in Parliament was a more direct way of influencing policy-making. That’s when you have the chance to speak to a much wider audience through the media, and you hope the media will carry the points you repeatedly raise and talk about. It was tough—the arts is not something talked about much, but I found it hugely meaningful and impactful. Those who work in the arts are such a minority that we really need this platform to work with policy makers.

XIANGYUN: Did you feel vulnerable in that role?

JANICE: In many ways. It’s not like being in the PAP where there are people banding together to support what you say. NMPs are non-partisan and speak as an independent—it’s just you if you want to oppose a bill, and you can only hope for a portion of Singaporeans who feel the same way. Voting against the White Paper in Parliament was pretty scary. I felt very strongly that it needed more work, but there were 87 PAP members in front of me who said yes to it. It takes a lot of courage to just stand by your beliefs when you’re under so much pressure to conform.

XIANGYUN: It also puts you under a new layer of public scrutiny and attention. This isn’t like theatre where you’re playing a role—whatever you say is put on display and open for public criticism, as Janice Koh.

JANICE: Yes. Everything is subjected to scrutiny, from your views, appearance, and even how you interact with others. It takes some getting used to. Many potential candidates we looked at after my term had reservations because of how the job opens up your life to the world.

I think I am most vulnerable when I’m on stage.

XIANGYUN: Do you feel vulnerable on stage too?

JANICE: I think I am most vulnerable when I’m on stage. It’s a safe make-believe world that allows you to tap into your innermost fears and feelings, and to display them publicly. It’s ironic that you might not show your feelings to a particular person in reality, but you do it when you’re on stage… to thousands of people.

XIANGYUN: Even when the audience members don’t know that’s what you’re really feeling.

JANICE: Yes, and that’s why it’s ironic. And vulnerable.

XIANGYUN: What about as an Arts NMP, when there’s no make-believe? Did it stop you from expressing yourself?

JANICE: [long pause] I always said what I felt.

XIANGYUN: Did doing that achieve what you wanted?

JANICE: I didn’t want any regrets. I was aware that my term in Parliament was just 2.5 years—that’s 24 Parliament sittings and three Budget debates. The only way to go for me was to hit the ground running and max out every opportunity. I would say that I am satisfied with my time there. There were some changes that happened fairly quickly, and others that would take a much longer time. But my term also broke me in many ways. It was really difficult to juggle my time as a Parliamentarian, and still be a mother, and an actor. But I learned a lot, and I grew up.

XIANGYUN: What do you mean when you say you grew up?

JANICE: As an NMP, I had to be concerned about issues people cared about and have opinions on them. I was looking at policy-making and how society responds to change. I was part of influencing this change and at the same time dealing with the politics of it. It’s a very adult process of changing the world—it’s about doing something and looking at what could be done rather than just complaining. I found it a very valuable experience to be invested in the future of Singapore.

XIANGYUN: Why didn’t you continue for another term?

JANICE: I wanted to spend more time with family. It’s particularly difficult for female MPs because there’s so much dependency on them at home. It would be really stressful to continue. But we do need more female NMPs. Women who work while raising families need their voices and perspectives heard.

XIANGYUN: I absolutely agree with you.

JANICE: I can understand why very few women go into politics. It’s still very much an Asian patriarchy where the male brings home the dough. There needs to be a cultural change for more women to join both the workforce and politics.

XIANGYUN: Did you do any yoga during your term?

JANICE: It saved my life [laughs].

XIANGYUN: How so?

JANICE: It allows me to have time for myself. Even if it’s just 60 or 90 minutes on the mat, it’s breathing space that belongs solely to me. It also keeps me physically healthy. More importantly though, yoga teaches me to do your practice, and all is coming. There are many postures that you’d never think you could do, but you’re doing it five years later. I learn to see things as journeys.

XIANGYUN: Do you get bored with the set of postures?

JANICE: There is always something to work on and improve.

XIANGYUN: And your body is different every day.

JANICE: Yes. It’s a marathon and not a sprint. Those who set themselves timelines either get bored with Ashtanga yoga or end up getting injured. Your body takes time to adjust. It’s a process.

XIANGYUN: Like life.

JANICE: Yes, a lot like life. Overcoming my fears made me more willing to take on other things I was afraid of.

XIANGYUN: Does that help you accept failure?

JANICE: Not failures per se, but that you have to fail to get it right. I’m a perfectionist and grew up in an education system that isn’t kind to failure. Yoga taught me that falling many times was necessary to find balance.

XIANGYUN: How do you think failures transform you?

JANICE: [pauses] That’s a difficult question. Failure is such a big word and I don’t see the downsides of failing—only learning points from mistakes or things that didn’t turn out how you wanted them to. My life is full of rejections as an actor, but are those considered failures? Being subjected to them on a regular basis may have made me grow a thick skin, but auditions still remain difficult and vulnerable. It’s a craft that’s so tied to your ego. I just try not to hold on to it much. There are some “failures” that drive you to try harder, and some you need to let go. I’m a do-er and don’t brood over things. I move on instead and do something else or something different. I keep going.

XIANGYUN: What makes you jump out of bed now?

JANICE: Yoga and having to send my kids to school [laughs]. I’m out of bed by 6am.

Parenting is a complex job. It’s one of those things that you can’t anticipate.

XIANGYUN: It sounds like being a mother has really shifted your priorities.

JANICE: It’s a process of learning. Marriage is about two people coming together with the ability to still lead individual lives and careers, but that changes when you have kids. Sacrifices have to be made; decisions and priorities change. I realised there are many things that are outside my control. It’s not possible to have things go my way with children. I had to learn to let go and see the bigger picture. Parenting is a complex job. It’s one of those things that you can’t anticipate. I’m still learning about myself every day—every little flaw and fault that no one ever pointed out to you becomes reflected through your children. I learn about how domineering I can be, my anger management issues, my impatience, and even how bad I am at listening.

XIANGYUN: How do you and your husband [Lionel Yeo] work as a team at home?

JANICE: My job is not 9 to 5, which means there’s flexibility to be home more as compared to Lionel. In a way, I take care of the micro details, while he looks at the macro—I also take care of the mundane everyday stuff like homework and being a high-class driver while he’s the more philosophical one. He has long talks with the kids about life, their behaviour, and what’s expected of them. I don’t take it for granted that there might be months when I’m off to a different universe, and Lionel understands that. Making art can be extremely consuming and demanding of time, energy, bandwidth and focus.

XIANGYUN: Will there be a day when you decide it’s time to stop acting?

JANICE: There might. I never say never. It’ll be time to stop when I no longer find joy in it.

XIANGYUN: If you had a superpower, what would it be?

JANICE: I once said teleportation for selfish reasons—I always feel like I need to be at different places at different times.

XIANGYUN: And now?

JANICE: I’d like to be able to make people happy.

XIANGYUN: What if you could change the world in three ways? What would you choose to change?

JANICE: Off the top of top of my head: Child trafficking—so much more needs to be done especially in Asia. Climate change—Singapore’s role can be hugely improved. We give a lot of lip service but don’t act on it; we don’t even take recycling seriously. Equality for those who are different from us, change mindsets about migration and be inclusive of LGBT people. Our world now needs more empathy, inclusivity and the understanding of differences. I feel like it’s closing up, which is a sorry state to be in after eight years of Obama. It’s particularly poignant and pertinent in the wake of the Brexit vote—it seems like the world is moving towards more borders as opposed to being open to diversity.

XIANGYUN: Finally, how would you like to be remembered?

JANICE: As a great mother, as a great friend, and as someone who brought people together.

XIANGYUN: Three really hard roles.

JANICE: Yeah, but it is not unachievable.

****

Edited by Wy-Lene Yap