Is a V-Shaped Economic Recovery Too Optimistic?

After a 30 per cent fall in S&P 500, Dow Jones and the NASDAQ, analysts and financial pundits have speculated on the possibility of a V-shaped recovery in the markets. But what are the probable chances of it happening? In this virus-ravaged economy, where both demand and supply have all but evaporated, an immediate normalisation of business activity seems unlikely. Amid global lockdowns, many companies have no revenues and a cost base that is inelastic. In the absence of liquidity, it is expected that a swathe of firms will not see the light of day. The markets have priced in the immediate effects of the coronavirus, but what about the second-order and third-order effects which are so hard to predict?

Knock-On Effects

The fact that Boeing has to draw on its available credit line of US$13.8 billion, highlights the current economic crisis. Additionally, reported layoffs in the U.S. reached a high of 11.4 million in March 2020 versus 1.8 million in the previous month—making an already tense situation worse for the working-class population. Everything points to a fall in demand for goods and services, save the essentials (like toilet paper). Even famous restauranteur David Chang of Momofuku had to close two of his restaurants due to Covid-19.

We are going to see more of this as restaurants and other small businesses start to default on their rental, mortgage and debt payments. Cash-positive businesses like cinemas and hair salons may not survive too. AMC Entertainment, a cinema operator in the U.S., was rumoured to be on the edges of bankruptcy. Caught between a rock and a hard place, it executed on an emergency bond issuance worth US$500 million at a hefty interest rate of 10.5 per cent.

Problems will start at a micro-level and eventually morph into something more sinister, triggering a chain of events that flows upwards to landlords as well as financial institutions who have given out loans to many of these small businesses. Just like the 2008 Financial Crisis, central banks and banks have a part to play in stabilising the economy, like practising forbearance by allowing debtors flexible payment options. Some creditors may be holding on to worthless assets as debtors default on their loans, and these accounting items on the creditors’ (banks) balance sheet would have to be written down. So far, we have not seen this happen in a big way. But oil’s fall from grace into negative territory may ignite another barrage of sell-down in the markets. Shale oil producers in the U.S. have large debt balances relative to operating cash flows, which may trigger a wave of defaults within the oil and gas industry—potentially causing some banks to falter.

Take Apache Corp, an independent oil producer, for instance. In FY 2019, the company had only US$65 million in EBITDA and US$8.5 billion of long-term debt, targeting cash-flow neutrality only if WTI oil prices hit US$53 per barrel. With current prices at around US$33, being profitable is a distant dream. The survival of Apache Corp and many other companies alike hinges on the duration and severity of Covid-19. However, with public and private sector debt at an all-time high, the next six months will be a bloodbath.

Unemployment

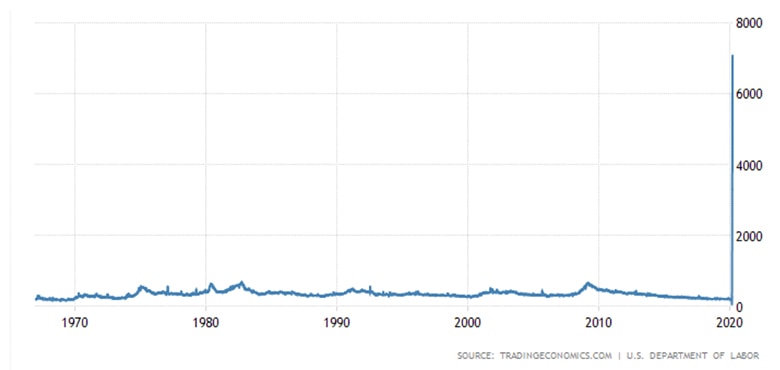

United States Jobless Claims; Source: US Department of Labour & Trading Economics

United States Jobless Claims; Source: US Department of Labour & Trading Economics

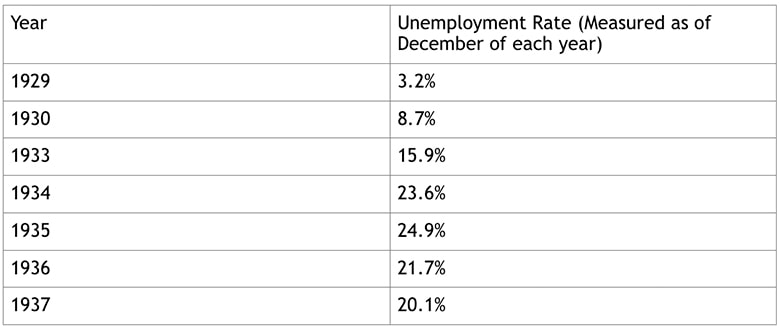

With the uncertainty in today’s markets, it should come as no surprise that U.S. unemployment is forecast to be higher than pre-coronavirus levels. During the 1929 Great Depression, the unemployment rate was a mild 3.2 per cent before peaking at 24.9 per cent in 1933. The situation seems far worse today. According to a survey done by the National Association of Bureau Economics, the projected unemployment rate in the U.S. would come close to 10 per cent in 2020 (higher than the reported unemployment rate in 1929), then taper off to 6.1 per cent in 2021. These projections are somewhat optimistic, because we might see unemployment trending higher over the next few years even as the Fed injects more money into the economy. In April alone, the U.S. jobless rate surged to 14.7 per cent. Printing money will not bring back consumer demand in the absence of a vaccine.

We can already see the damage done to the global economy, and these are just the first-order effects. The full scale of the damage is hardly predictable and noticeable immediately. Charlie Munger, vice-chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, sums it up well when he says that “consequences have consequences.”

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics

Possible Cascade of Bankruptcies

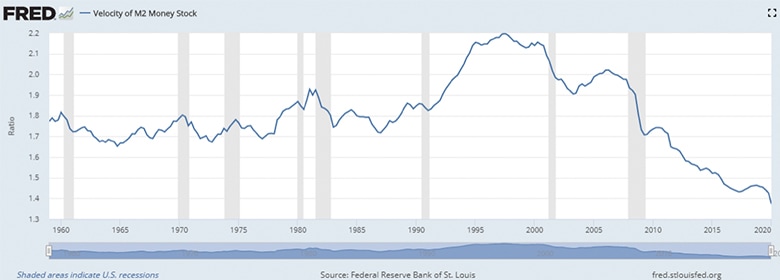

The unintended consequence of Covid-19 is a decreased velocity of money in the global economy. As such, there will be impending bankruptcies in the months ahead, unless a company is extremely well capitalised. Or with some government help, the probability of survival becomes higher.

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

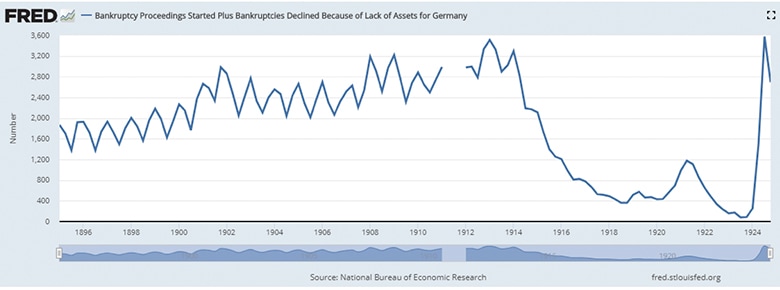

J.C. Penney, J Crew and Neiman Marcus, all well-known retailers in the U.S. have filed for bankruptcies, hoping to get favourable terms on debtor-in-possession financing to keep stores open during the insolvency process. According to analysts, J.C. Penny Co. Inc. had only seven months of working capital left when it filed for bankruptcy.

Across the globe, Virgin Australia also filed for bankruptcy in April as it entered into voluntary administration. Since the Australian government refused Virgin’s request for an AUD$1.4 billion loan, the company’s administrators are attempting to save the business by recapitalising it.

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

The idea that the next six months could see a recovery is almost preposterous considering the numerous unreported cases of small business going bust. Additionally, small businesses would have to bear the brunt of the crisis as government aid to them is typically inefficient. It is certainly easier for the government to deploy billions in loans to large companies via a convertible bond offering; this way, governments get paid when business normalcy resumes. But how would the government do that with small businesses? Your guess is good as mine.

A U-Shaped Economic Recovery Seems More Likely

A well-known economist Nouriel Roubini was quick to thrash any suggestions of a V-shaped economic recovery. He said that there would be a decline in spending while savings would increase from hereon, as companies and consumers scramble to deleverage from high levels of debt. Capital expenditures will decrease for a stretch of time as the global economy enters an investment slump. From his vantage point, Roubini sees an anaemic U-shaped recovery and, at worse, an L-Shaped recovery if things go south. There might be a resurgence in the spread of the virus when countries begin to relax their lockdown measures. Reports of new clusters have surfaced from Wuhan, China, as the province reopened for business. South Korea has also reported a new cluster of infections caused by a 29-year old man who visited three nightclubs.

In light of these events unfolding, I am of the view that things are going to get worse before it gets better. No one knows how long and deep this recession will be. But it is probably wise to ask ourselves what is next, as the second-order effects of the coronavirus kick in.