Luckin Coffee and the Alchemy of Fraud

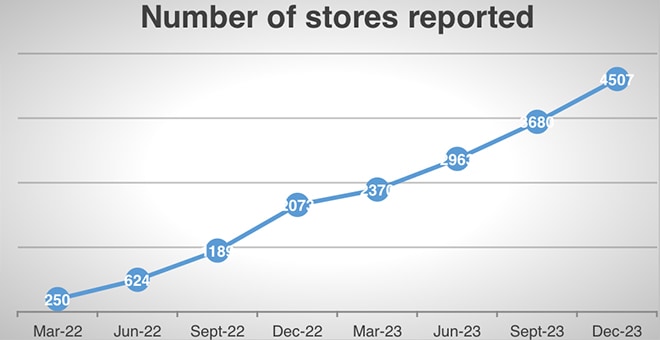

The story seemed to line up. A unicorn in the making that would rival Starbucks in an ever-growing market such as China would be captivating to investors far and wide. Founded in 2017, Luckin Coffee went all guns blazing, opening 2370 stores in 28 Chinese cities within 18 months. And it didn’t take long for its growth plans to appeal to the greed of America’s financial markets, which made the road easier to a NASDAQ IPO.

So, how did Luckin Coffee pull the wool over people’s eyes and reach an IPO in two years while established giants like Twitter, Uber and Starbucks took 7, 10 and 21 years respectively? By weaving a web of financial lies.

For the fiscal year of 2018, Luckin reported a revenue of US$122.1 million. And when it listed on NASDAQ in May 2019, the market capitalisation was US$2.24 billion. The valuation was astronomical, which meant that the company was trading at 18 times its sales revenue at the time of the IPO. Comparatively, Starbucks now trades at a price-to-sales ratio of 3.41. In that same fiscal year, the company gave a dividend of US$1.44 per share—amounting to a dividend yield of around 2 per cent. But Luckin never did, and I don’t think it ever intended to do so. Additionally, the operating expenses for 2018 amounted to US$192 million, which raises the question of whether the managers were overpaying themselves.

A year later, Luckin racked up general and administrative expenses of US$78 million for the third quarter of 2019, an increase of 108 per cent in comparison to the same quarter in 2018. The company attributed this dramatic increase to business expansion and share-based compensation for senior managers. These expenses also represented 16 per cent of the net revenues for the third quarter. Starbucks, on the other hand, had general and administrative expenses of US$1.4 billion to US$1.9 billion from 2016 to 2019, representing between 6.4 per cent and 6.9 per cent of revenues. Much of Luckin’s residual cash flows if any, probably went to its senior managers.

If you analyse Luckin’s business model, it was not sustainable to begin with. The company subsidised coffee drinkers at the expense of shareholders, by giving significant discounts on coffee sold. Each cup of coffee cost approximately US$1.50, which was significantly cheaper than Starbucks’ US$4.30 per cup. Gross margins for the quarter ending in March 2019 were negative 16.65 per cent before turning suspiciously positive in the next two quarters—10.4 per cent and 48.2 per cent respectively. (This modus operandi can be seen in companies who want to dupe investors. If you want to “suck” money out of unwitting investors, at least report a couple of good quarters before doing so.) In January 2020, the company decided to do a secondary placement, raising US$1.1 billion from investors—sending a message to the market that it was doing phenomenally well.

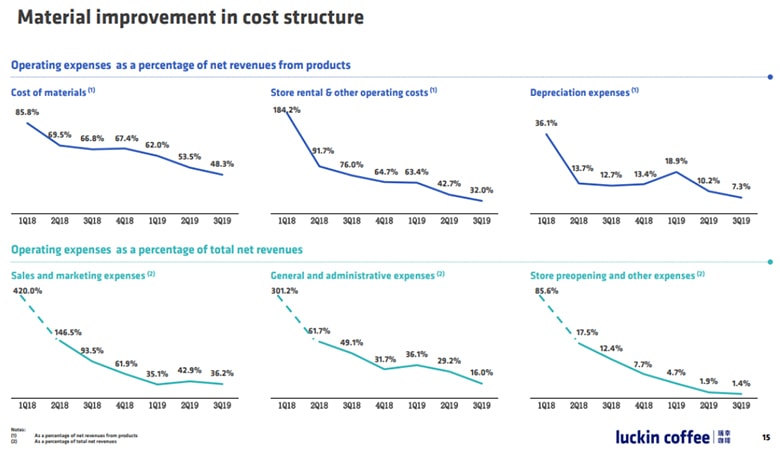

Founders Jenny Zhiya Qian and Charles Lu Zhengyao always knew what investors wanted. Hence, they kept spinning stories of growth and a magical reduction in expenses, and voila! You get a rising share price.

Source: Luckin Coffee 3Q2019 Presentation

Source: Luckin Coffee 3Q2019 Presentation

Usually, operating expenses as a percentage of sales revenue can be predicted with some degree of accuracy. But in the case of Luckin, it reported a “material improvement in cost structures,” even as the company opened more stores. Sales and marketing expenses fell from 420 per cent in 1Q2018 to 16.2 per cent in 3Q2019.

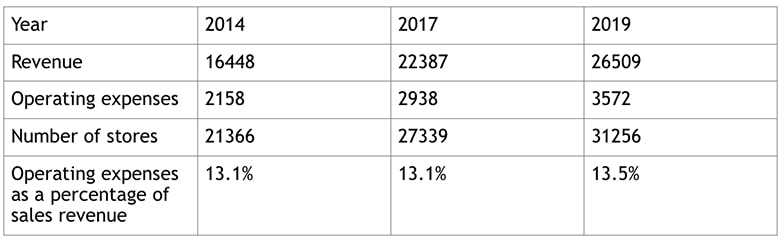

Starbucks’ Financials: Figures in millions USD/ Source: Morningstar

Starbucks’ Financials: Figures in millions USD/ Source: Morningstar

It is normal for operational costs to grow in tandem with sales growth (store growth) as you can see in Starbucks’ reported numbers. Yet Luckin’s operational costs (as a percentage of revenues) were falling over the quarters as it announced a growth in the number of stores. This was the biggest tell-tale sign that the company was fraudulent.

Source: Luckin Coffee Filings

Source: Luckin Coffee Filings

As investors bought into the prospect of profitability, Luckin Coffee’s share price lifted to US$50 per share. But not for long. An anonymous short seller’s report began to circulate online in early February 2020, causing the share price to plummet to US$2.50. At that price, the implied market capitalisation was still US$650 million, which meant that investors were paying approximately 5.3 times the sales revenue recorded in 2018, for a spurious company that fabricated US$310 million in sales.

It is not uncommon knowledge that many Chinese companies who seek access to capital markets have no intention to grow the business. They have a different agenda of wanting to cash out and are surrounded by the usual collaborators who want a slice of the pie. Investment bankers, auditors and other consultants are incentivised (every step of the way) to prepare for the IPO while “looking the other way.” Essentially, the fees earned are in direct proportion to what is raised in an IPO—and this percentage works out to be between 5 and 7 per cent plus around 30 to 50 per cent of first-day profits from clients of investment banks that were allocated with shares.

In the case of Luckin, the overpromised growth story and sky-high valuation served a few bedfellows that were privy to the IPO’s inner dealings, but not the ordinary retail investor.

Another common malpractice of Chinese companies is having two sets of accounts—one for public matters and another for internal use. This isn’t new, and investors have to be wary of Chinese companies who list in foreign markets such as Hong Kong, China, the U.S. and Singapore. During one of my investigations into Chinese companies listed in Singapore, I found that not one, but a few of these companies, do not even have an investor relations contact person. The “Contact Us” page on their websites was blank; no emails, no addresses, or phone numbers. How can you trust such companies to take care of your interests if they are unreachable?

Questionable Board Members

Luckin’s board lacked the independence and ethics needed to manage a public listed company too. The co-founder and chief marketing officer Yang Fei was once sentenced to 1.5 years in prison for illegal business activity. But investors were too focused on the company’s unicon status to notice these red flags.

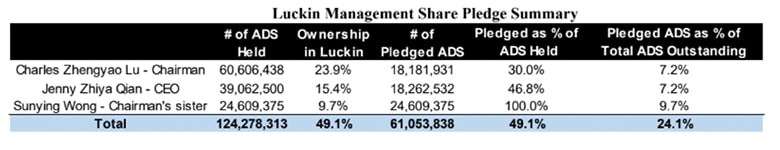

Source: January 8th Prospectus

Source: January 8th Prospectus

It was reported that Lu had pledged shares to financiers to obtain a loan. For whatever reason the loan was for, it did not make any sense. The IPO was not just a partial exit for Lu and early-stage investors—it was also to provide capital to grow its business further. But the fact that Lu cashed out of the company at breakneck speed via share pledges showed his hand.

From the company’s reported financial statements, the board of directors cashed out approximately 49 per cent of their holdings through these stock pledges. This is not Lu’s “first rodeo” so to speak. In 2016, Lu and a group of private equity investors cashed out of CAR Inc. (699.HK) to the tune of US$1.6 billion in profits, while most public shareholders bore the brunt of the losses. Subsequently, Car Inc’s share price fell almost 86 per cent to date.

Fast forward to the present day, these share pledges have led to a 95 per cent decline in Luckin’s share price. As Lu defaulted on US$158 million of margin loans, lenders had to scramble to sell more than 76 million shares pledged as collateral. Although some might see this as a bargain, I would not touch it with a ten-foot pole for you never know what else lurks behind those “reported numbers.”