Market Thoughts About Descending Into a Messy Chaos

Watching the English market turmoil unfurl, making Bank of Japan’s forex intervention look like child’s play, while on English soil was quite an unforgettable experience after participating in the national mourning a week earlier. There was a sinking feeling in the pits of our stomachs, gripped by the thought that the late Queen symbolised the last bastion of stability and peace. Ominously enough, the markets unravelled right after her state funeral and we returned home to financial market chaos.

What could possibly be more thrilling than any Netflix horror flick on cannibals and zombies other than a Lehman moment on a Monday, except that it is just Credit Suisse (again) whose chairman happens to be Axel Lehmann? Only to face a full-blown risk-on rally in less than 24 hours?

It is just as well that we are back from driving in the U.K., navigating a country of roundabouts. Encountering those ginormous ones with five exits to tiny ones the size of a dish and the simple crude circles painted in the middle of an intersection does make us perfectly suited to confront the challenges of the financial markets this week.

This will be a short note to recalibrate our minds because we are not much invested these days except for government bills as the volatility has been dizzying and we are learning to live with oxymoronic headlines like “Wall Street Fell Sharply Following a Solid September Jobs Report…”.

How about our favourite quote ripped off from FinTweet? “If your model does not include a pandemic, nuclear war, record inflation, full employment, no central bank puts, housing roll-over, hawkish monetary policies, negative GDP, strong US dollar and climate shenanigans, you are NGMI.” (*NGMI = Not Gonna Make It)

All signs point to a “financial accident” waiting to happen as Scott Minerd of Guggenheim Partners puts it—and it is what markets have come to—a big, messy chaos, quite unhinged, if you ask us. The alarming conclusion is that the adults have left the room with no one in charge of the runaway train. We have hedge funds reaping 193 per cent on the year when central banks like the Reserve Bank of Australia sit on negative equity like it is perfectly normal for central banks to be insolvent.

Bloomberg estimates that US$36 trillion has been lost in global bonds and stocks this year as of the 30th of September while other estimates think it is closer to $50 trillion. This is not counting the loss of purchasing power from raging inflation which means people are buying less at higher prices to show for those positive retail sales figures.

For one, retail spending has fallen off a cliff in many parts of the world with Nike and gang coming out to warn of sharp increases in inventory because people have just stopped buying stuff to focus on more important necessities.

Mortgage rates are at a 16-year high in the U.S. and levels not seen in over a decade in Singapore, so what is missing in the big picture? And why is it different this time?

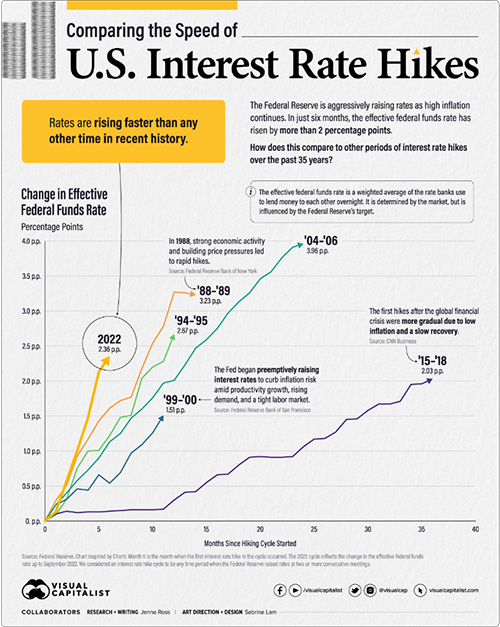

It has never happened so fast and furiously in recent history and this has simply caught us off guard.

Interest rates

From 2015 to 2021 long-term interest rates sat at record lows. On average, during this period, 10- year bonds yielded 1.9 per cent in America, 1.1 per cent in the U.K. and zero in Germany. And just as investors got used to the idea of low rates, in 2022, America’s yields have risen from 1.5 per cent to 3.8 per cent, U.K. from 1 to 4.1 per cent and Germany from -0.2 per cent to 2 per cent. A friend shared that his mortgage rate rose, without much warning, from 2.18 per cent to 3.52 per cent within three months. How is that for a shock?

Source: Visual Capitalist

Source: Visual Capitalist

This week alone, we saw volatility unimagined with Australian bond yields moving over 0.25 per cent in a day after a central bank surprise.

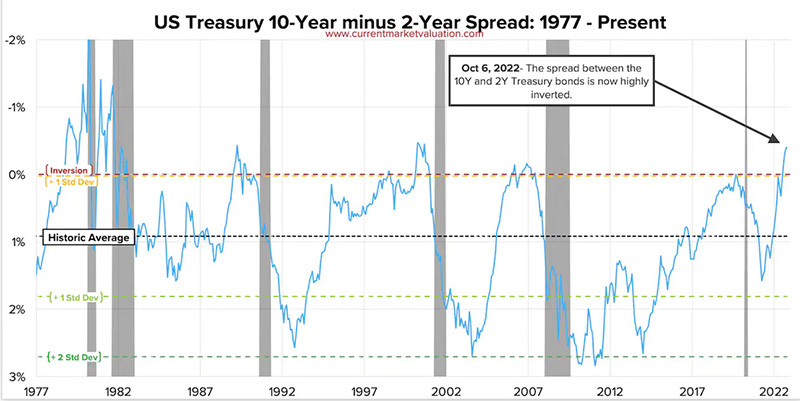

Even worse is the yield curve inversion which many would have noticed by now, that the short-end rates are higher than long-end rates which do not occur typically and have historically been a precursor to a recession. We have not had such a prolonged inversion of such magnitude since the late 1990s which is, again, as ominous as it gets.

Source: Current Market Valuation

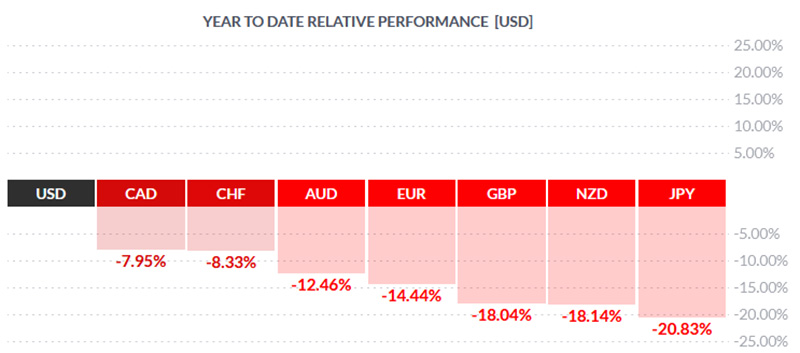

Foreign exchange

The Japanese yen has lost a fifth of its value so far this year against the US dollar and hit a 24-year low while the British pound has hit a 37-year low which both cannot beat Bitcoin’s 58 per cent collapse.

It is all about U.S. monetary policy now.

The narrative just a year ago was for transitory inflation and we had eminent economists in the FOMC like Neel Kashkari convinced that inflation will weaken until May this year before a full pivot this week. The U.S. Federal Reserve is “quite a ways away” from pausing rate hikes when the rhetoric is fast switching to recession probabilities now to throw in economic uncertainty on top of monetary policy stalemate.

We have enough drama to wear us down daily which brings us to the other glaring uncertainty—political uncertainty: both geopolitical tensions and domestic politics as countries start to fray from within as we approach the American midterms. Nobody knows what to expect anymore.

Perhaps it is no wonder they are about to legalise cannabis in America. Let the people smoke themselves numb?

Financial stability is severely threatened and investors are fleeing to cash, the most since April 2020, according to Bank of America and there is no quick fix for that.

Let us discuss it from another angle which is also our greatest fear and that is collateral. Collateral is an asset that a lender accepts as security for extending a loan as defined by Investopedia.

US treasuries are at the apex of global collateral pools be it repo markets or for the derivative markets’ CSA (Credit Support Annex) as bonds also serve as collateral in portfolio lending from financial institutions to retail accounts. When the value of the collateral shrinks, a margin call will be triggered and the borrower will have to top up the collateral or liquidate their assets.

It stands to reason that the overall borrowing capacity for global financial markets is greatly reduced as a result of higher interest rates, not to mention the higher borrowing cost.

That has a spillover effect on liquidity or money supply and we have absolutely no idea where this will lead us to.

The other more implicating problem would possibly be the loss of another type of liquidity, that is market price discovery, which has become a big enough problem for Bloomberg to point out this week. It is getting harder and harder to buy and sell the biggest collateral used in the world, US treasuries. We can assure you that the problem exists even for small amounts of corporate bonds and stock market liquidity is just as bad, which is leading to more volatility. There is just no demand or supply when you need it because it has become a one-way street.

The only solution to all this points to central bank bailouts (for demand) which the markets have gotten too used to since Lehman. With QE2 and QE3 and the Covid pandemic stimulus packages, we see the central bank “put options” which happened again just two weeks ago with the Bank of England when they had to step in to buy long bonds, purportedly to save the pension fund.

It will be hard to make a call but as with all bailouts, something has to break first. But before that, we will have the US CPI next week and a lot more messy chaos to come.