Why Shareholder Activism in Asia Needs to Be Embraced by Investors

The US in the 1980s had a reputation for being the decade of greed, as the era was rife with corporate raiders and activists trying to defend their shareholder rights. Activists targeted undervalued companies which were run inefficiently and some were taken over forcefully. The management of these companies were goaded into doing a better job, or at the very least, forced to return excess cash to shareholders in the form of a share buyback.

These corporate raids were largely facilitated by the ever infamous Michael Milken, a financier whom corporate raiders looked to for junk bond financing arrangements. The rationale was simple. A target company with highly predictive cash flows and a sub-optimal capital structure could be levered up to finance an acquisition or a hostile takeover. The effect would set into motion both management and market participants, eventually producing value for minority investors and control investors. However, for some, these ambitious corporate raids have resulted in public failures for too much high yield debt was used to finance some of these takeovers.

These days, ‘hostile takeovers’ have morphed into a milder version called ‘shareholder activism’, usually on a scale smaller than an outright acquisition. Many shareholder activists with sizeable stakes seek change in public listed companies by making their opinions heard in the media and oftentimes, having a conversation with the managers of the company.

Why does shareholder activism work? It all boils down to a very basic idea around the principal-agent conflict. Agents or managers want to work to pad their pockets and because of such incentives, make poor management decisions which retard value creation within a company. GameStop’s financial performance has been on a decline but the managers have opted to perform share buybacks instead of paying down debt, which is weighing down on its balance sheet strength. In FY 2015, the company issued $351 million of debt and repurchased $331 million of stock. Had the share buyback not gone ahead, the company would have saved on interest expenses and strengthened its capital structure further.

How rational is a share buyback in times when a company is gradually suffering from a lack of robustness in its business model? Earnings per share increased from $3.47 in FY 2015 to $3.78 in FY 2016 before falling to $2.93 in FY 2017. Hence, the argument that share buybacks would increase its earnings per share does not hold weight here. This is the classic agency-principal conflict at work. Shareholders (the principal) need to voice up and rectify such conflicts.

The Efficacy of Activism

In research entitled “The Returns to Hedge Fund Activism” conducted by participants from Duke University, Columbia University, Vanderbilt University and the University of San Diego, it was found that hedge fund activism targeted at improving operating performance has been largely positive. The study involving 236 hedge funds and 882 target companies from 2001 to 2006, showed that hedge fund activism does affect stock prices and impact outcomes positively. In general, the target firms experienced abnormal returns of 2% on the announcement day and 7.2% over 20 days. These firms also have improved operating performance, an increased payout and higher CEO turnover.

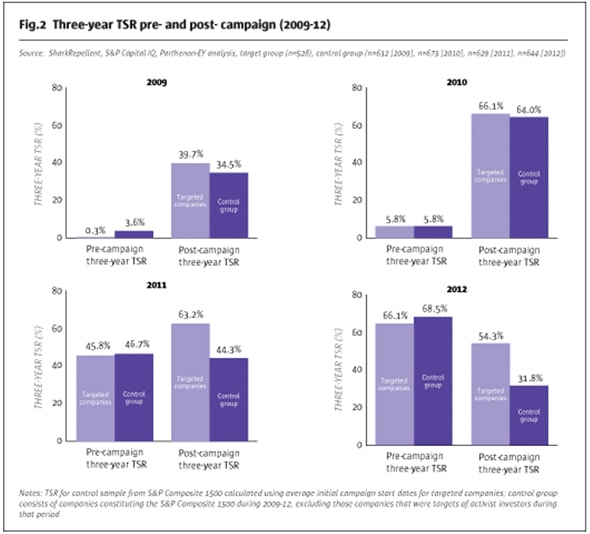

Another study, “The Long Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism” looked at 2040 activist interventions from 1994 to 2007. The target firms in which activist investors acted on outperformed the market and its peers over a 3 to 5 year period thereafter. Yet another study done by SharkRepellent showed that total shareholder returns tend to exceed that of the control group.

Source: The Hedge Fund Journal

Source: The Hedge Fund Journal

If shareholder activism has an effect on corporate values, why is shareholder activism not as popular in Asia as compared to the US? There are various reasons, but the one thing that comes to mind is culture. Asian fund managers are generally known to be less confrontational.

Asia is also playing “catch up” with their western counterparts. Effective boardroom structures, corporate governance, efficient capital allocation all take a backseat to cronyism, in group or family-controlled shareholder structures. These entrenched ways often lead to a “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” type of situation. That is perhaps one of the reasons why valuation multiples in Asia remain much lower than the US.

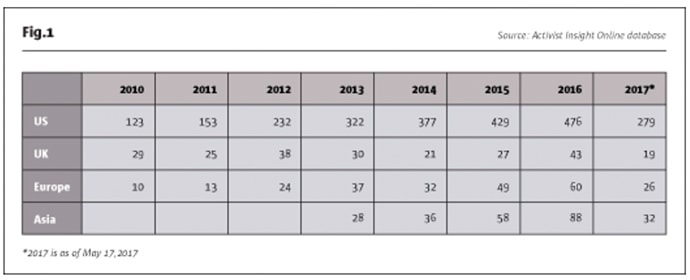

Source: The Hedge Fund Journal

Source: The Hedge Fund Journal

Regardless, the trends towards shareholder activism have been increasing but still lag behind the US. For example, in 2017, there were 279 activist campaigns launched in the US while only 32 were launched in Asia. This wide gap signifies that there is more room for shareholder activism in Asia.

Activism in Small & Medium Capitalisation Companies

While not all activist campaigns result in tangible success as measured by academics, it is also true that small-cap value stocks tend to outperform large-cap value stocks and statistically undervalued stocks tend to outperform growth stocks. This is evident from the research done by Eugene Fama and Kenneth French. As such, it is my view that activism in smaller stocks will have a potent effect on enhancing shareholders’ value. For activist investors who wish to find alpha in today’s markets, Asia’s many undervalued small and mid-cap stocks are an abundant ground for such activist campaigns to unlock shareholder value.

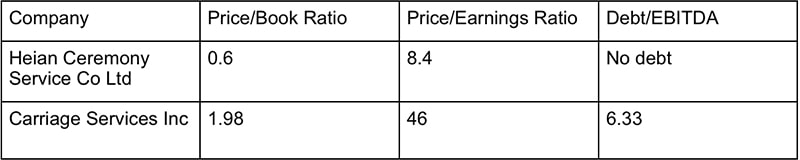

An example of this is Heian Ceremony Service (TYO:2344)—a company that provides wedding, funeral and welfare services to the Japanese market—with a market capitalisation of ¥11.7 billion. Due to the growing ageing population in Japan, the company is experiencing some mild but positive tailwinds, with its revenues growing at an annual rate of 2.5%. Despite that, the company’s share price has traded between ¥400 and ¥900 per share historically. The price to earnings ratio and price to book ratio stands at 8.4 and 0.6 respectively. A similar company, Carriage Services (NYSE:CSV) trades at a PE ratio of 46 times.

Source: Morningstar

Source: Morningstar

This is where it gets interesting. The average free cash flow per share of Heian Ceremony amounts to about ¥62.8 per share. On average, it has paid out a dividend of ¥19.3 per share. The company paid out ¥24 per share in FY 2019 and should be applauded for having increased its dividends over the years. But, an argument can be made that the company could increase the dividends paid to ¥40 per share for its cash reserves have increased from ¥6.6 billion to ¥10.8 billion over the last 6 years. Is the company keeping too much cash in excess of its working capital needs? I’m inclined to think so.

Asia’s capital markets are a rich source of small and mid-cap companies such as Heian Ceremony with an untapped borrowing capacity and a sub-optimal dividend payout ratio. If Heian Ceremony increased its dividends paid to ¥40 per share, the market would surely accord a higher market value to the company. Furthermore, its strong balance sheet makes it a company suitable for a leveraged buyout. Heian’s average EBITDA over the last 5 years was approximately ¥2.35 billion. If we estimate the company’s borrowing capacity to be 6 times of that number, the borrowing capacity of the company would be ¥14.1 billion, greater than that of the market capitalisation of ¥11.7 billion. This goes to show how undervalued some of the companies are in Asia—making a case for greater shareholder activism in the region.

Changes to Corporate Governance Standards in Asia

In the last 5 years or so, countries such as Japan, Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong have enacted new sets of stewardship and corporate governance codes. For example, in 2016, Hong Kong published a “Principles of Stewardship Code” that details best practices laid out by the SFC for investors who invest in Hong Kong-listed companies. In Japan, ‘Abenomics’, the Stewardship Code (2017) and the Corporate Governance Code (2018) continue to play a part in increasing shareholder and management engagement. In Singapore, the Investment Management Association of Singapore issued a paper entitled “Singapore Stewardship Principles” to encourage responsible investing. These developments and more, led by the respective authorities of each country would pave the way for disrupting the status quo in Asia, and perhaps, create greater shareholder value for companies in Asia. As Asia wakes up from a slumber and shareholder activists go to work, corporate values will improve.