Should We Take Instagram Poets Seriously?

There are two ways to be a commercial hit in the literary world: you could either be dead or be a social media star. My fascination with deceased poets began with Sylvia Plath at the age of 12. It was not so much her literary prowess that captured my fancy, but rather the way she tragically perished by sticking her head into an oven. You could say my priorities (or interests) were clearly misplaced, and somehow this morbid little nugget of knowledge inspired me to embark on a lifelong exploration into the enthralling world of poetry. From analysing structure and meaning in William Blake’s poems to tortuously dissecting 24 whole chapters of Homer’s Odyssey, the written word roused my imagination and faculties in a way no other medium of art had before.

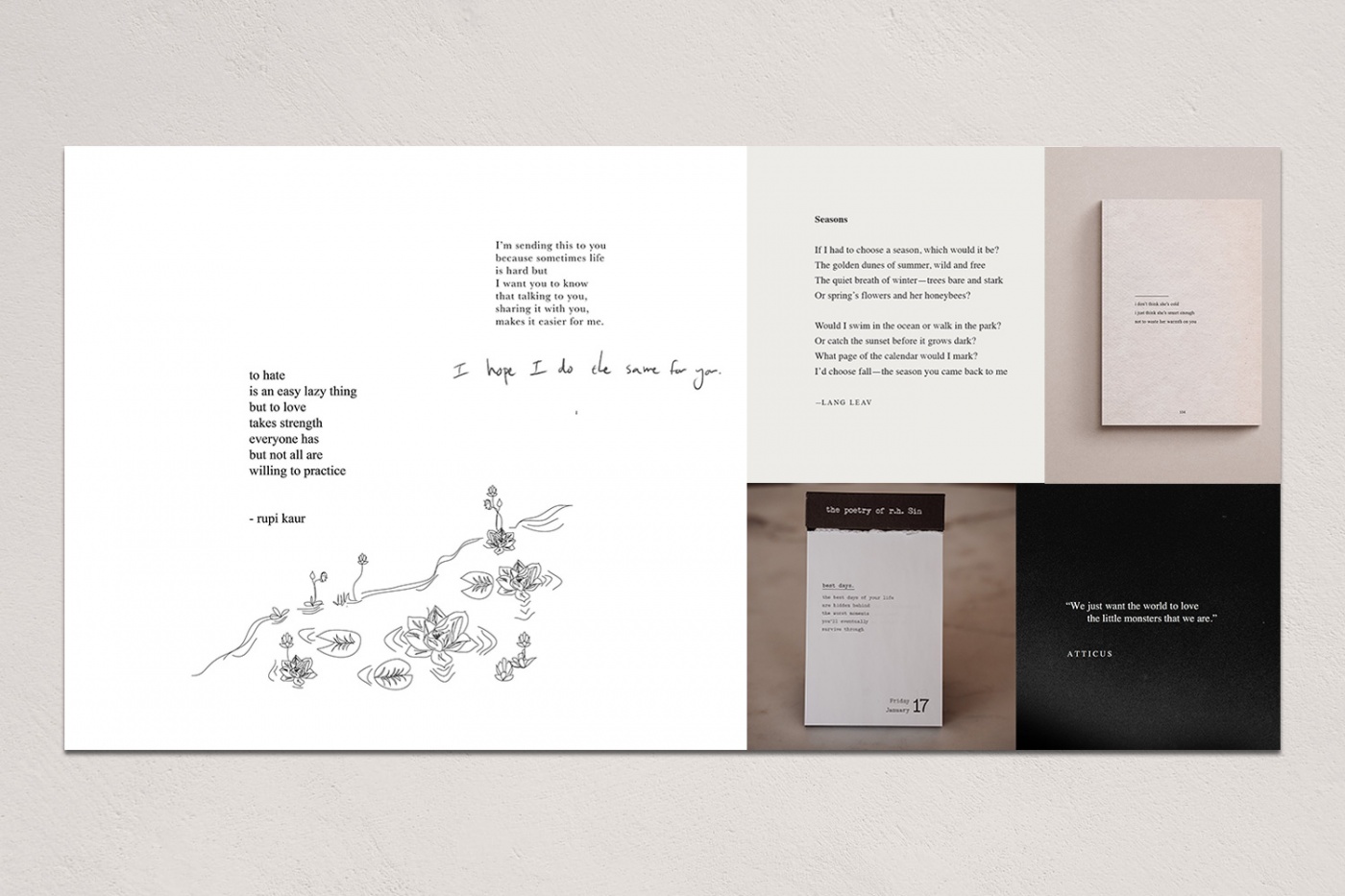

On one life-changing day in 2015, I sauntered into Urban Outfitters in New York and from the corner of my eye, spied a book of poems entitled Milk and Honey. It was my inaugural initiation into the world of Rupi Kaur, often regarded as the frontrunner of a new legion of “Insta-poets.” When I casually flipped the book open, the first poem that caught my eye read: “I do not need the kind of love that is draining I want someone who energises me.” And that was it. A one-sentence poem. It was a watershed moment. This was poetry? Was I missing the point? The next quote I chanced upon said: “Don’t mistake salt for sugar if he wants to be with you he will it’s that simple.” I was genuinely perplexed. Who the heck was this woman? The female answer to British life coach Matthew Hussey? Did she just single-handedly crack the male code? Her bon mots had the casual tone of Whatsapp messages containing self-learnt man wisdom, that I would regale my female friends with, at 3 a.m. after a few lychee martinis. Yet the ingenuousness of her one-liners was unfamiliar to me; they were an antithesis to the villanelle poetic form. Perhaps, that was the whole point. Kaur’s free verses weren’t meant to be obscure or intimidating.

Traditional poetry has long been perceived as residing in an esoteric realm, decoded only by highbrows and intellectual snobs. Whereas Instagram poetry is a bite-sized, instant gratification fix for the bourgeoisie, with none of the complexities and nuances of the epics. There is a level of emotional relatability, with vocabulary that eschews elaborate metaphors and alliteration. The phenomenal success of 27-year-old Rupi Kaur is a shining example of how poetry has evolved dramatically since the days of Emily Dickinson. She has four million Instagram followers (including Ariana Grande) and her literary debut Milk and Honey sold more than 3.5 million copies, beating the likes of Homer, whose acclaimed works are a paradigm of literature. The Indian-born Canadian poet published her first book while she was still in college in 2014, and made the New York Times best-seller list in 2016. To some, her poetry, which speaks of trauma, self-love and quintessential romantic relationships are seen as cathartic and empowering. And to others, her poems are run-of-the-mill, bromidic, and vapid.

Apart from Kaur, there are a growing number of Insta-poets who have achieved mainstream fame: r.h. Sin, pleasefindthis (Iain S. Thomas), Cambodian-Australian poet Lang Leav, self-taught writer Beau Taplin and the enigmatic masked poet Atticus, who has 1.4 million followers on Instagram. Social media has revitalised an antiquated genre of self-expression for a new audience and is galvanising a renascence in poetry book sales globally. The NPD Group, Inc., an American market research company, cited that twelve of the top 20 bestselling poetry authors in 2017 were Insta-poets. Being artistic isn’t enough anymore. These distinctive verse-makers are also enterprising and ambitious. Kaur, who says her poetry is like “running a business,” earns money from live events and publications. Atticus’s website has an e-commerce component where fans can purchase merchandise such as shirts from his Stay Wild Collection inscribed with his notable words. His most celebrated and tattoo-able poem is a pithy two-line aphorism: “If I conquered all my demons there wouldn’t be much left of me,” which is easy to spout during loathsome days.

In spite of Insta-poetry’s burgeoning popularity in the last four years, I am not quite a convert yet. This subgenre has stolen the pleasure of poetry away from me. The joy of reading poems is like the slow undressing of a secret. I relish the way my heart palpitates as I fall deeper into the sea of words and allegories, eagerly peeling away the layers like an artichoke and uncovering the hidden meaning of symbols. I don’t get that when I read Rupi Kaur, who sorely lacks intrigue despite giving off an impression of profundity. Consider the simplicity of Ezra Pound’s two-line poem “In a Station of the Metro”: “The apparition of these faces in a crowd; petals on a wet, black bough.” The brevity of the poem is deliberate, to mimic the rapid pace of a train speeding by, and imbued with an incisive depth which Kaur lacks. Pound doesn’t need doodle-like drawings; his compelling subtext about the ephemerality of human life and the tragedy of impermanence creates a cerebral space for reflection.

Although one can argue that the commodification of poetry has adulterated the quality of verse, there is still inherent value to be gained from Insta-poets. The majority of them dish out other positive advice on living a better life, leaving toxic relationships and loving oneself—rules of the 21st century. Atticus has people thanking him for his poetry, saying that it has helped them overcome depression and self-injury, while aspiring writers regard him as a beacon of inspiration. For those nursing a broken heart, Taplin will comfort you like an experienced best friend who knows that “if it hurts more than it makes you happy, then take the lesson and leave.” Hoity-toity-ness aside, Insta-poetry may lack the innuendo and intricacy that literary-minded critics adore, but its ideology resounds with a modern audience, who have no desire to contend with the complicated jumble of allusions and symbolism of the traditional form.

Like all things, poetry has to adapt to the changing world in order to not get lost in the dust. Perhaps to appreciate the value of Insta-poetry, we need to understand that its function is fundamentally different from that of Petrarchan sonnets. Think of it as a more palatable, inclusive style of literature for all, where the words are meant to be understood and circulated. If the arts are supposed to be subjective, then no one really has the power to decide what makes “good” poetry. Its appeal may very well be to make us feel good—and heard. So tonight, instead of libations, I will allow myself to be intoxicated by the words of Lang Leav’s Love & Misadventure and use William Carlos Williams’ line, “Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold,” to justify my guilty indulgence.