Lang Leav: A Poet for Our Time

If Lang Leav were a literary character, she would be the spunky and spirited Jo March from Little Women. Why? Maybe it could be Leav’s headstrong and independent nature, her desire to wander, or her insatiable curiosity, coupled with a burning desire to do something extraordinary with her life—qualities that her elders lauded in boys, but frowned upon in girls. In spite of this, the dauntless young adolescent took it all in her stride, knowing she was destined to be different.

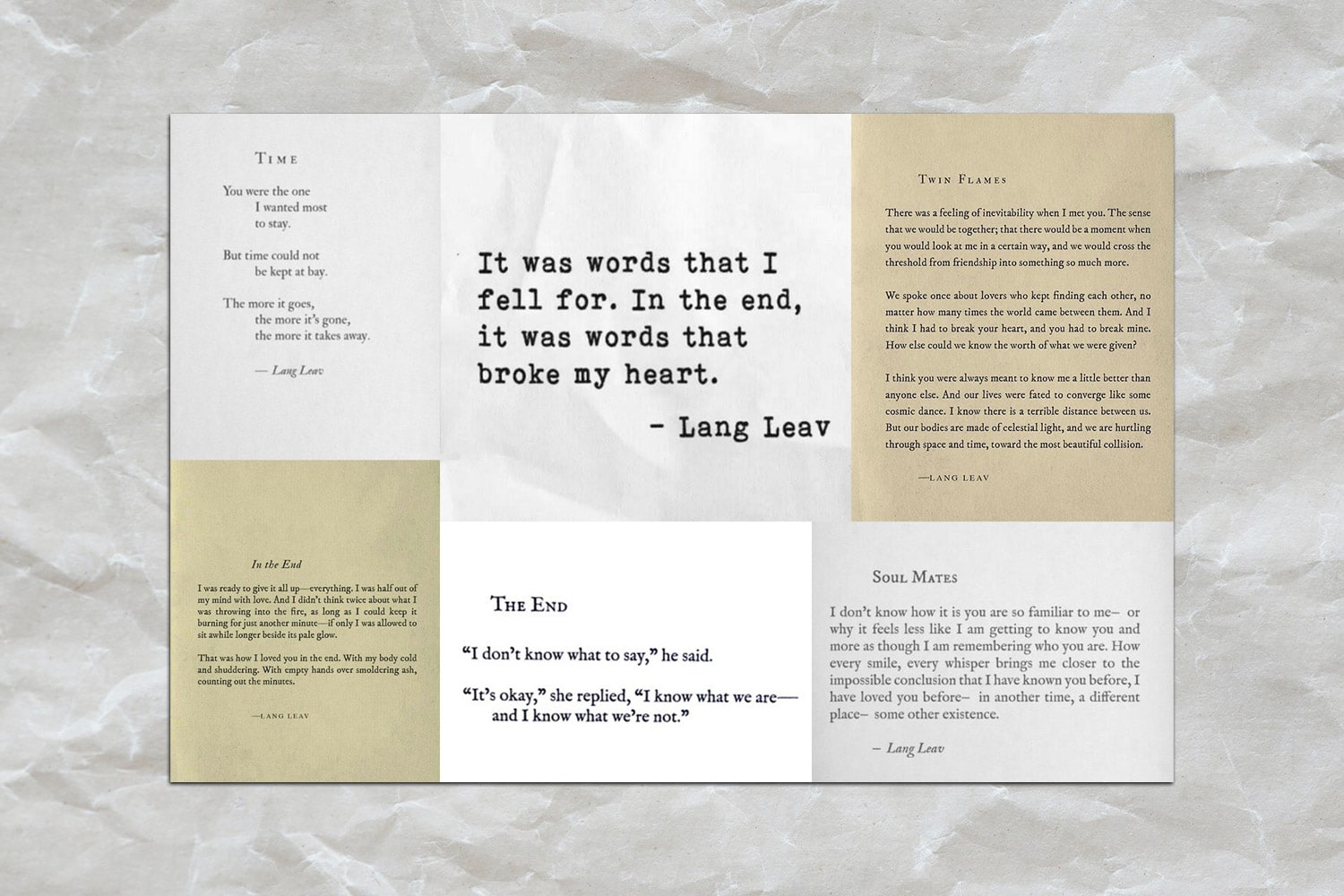

When I first chanced upon best-selling author Lang Leav’s debut poetry collection, Love & Misadventure, in 2013, it was the unadulterated veracity of her words, untinged by the simplicity of her verse that struck me. Even to this day, I’m able to recite lines like, “It was words that I fell for. In the end, it was words that broke my heart.” While you may find it melodramatic, that was an accurate (and concise) account of how I felt after experiencing an acrimonious breakup. Like a fat kid who was addicted to junk food, Leav’s poems were my guilty pleasure and I would voraciously consume her words in the solitude of my room. Perhaps it was the way she distilled raw emotions with clarity and lucidity that made her work so compelling. Or how she addressed heartache and abandonment in an untrammelled manner that resonated with my soul. From limerence to the affliction of lost love, Leav has covered all the bases.

The University of New South Wales alumna is no stranger to pain and heartbreak. Born in a refugee camp in Thailand to Cambodian parents, her family left for the migrant town of Cabramatta, Australia just before she turned one. Although her childhood was a relatively happy one, Leav grew up with other migrants from several war-torn countries and found herself immersed in their collective sadness and despair. Since young, writing was a form of escapism for her; it wasn’t so much a choice as it was a necessity. Leav always knew she wanted to be a writer, with the liberty to create an alternate, imagined universe.

Despite the affecting candour that goes into her poetry, Leav is quite an enigma. The deeply private author, who guards her personal life fiercely, including her highly controversial relationship with fellow wordsmith Michael Faudet, whom many have said could have been a figment of her imagination (he’s not), enjoys a peaceful life in their cosy house by the sea, where they write books. This reclusive side is a stark juxtaposition to her visceral presence on social media, where her love poems have become manifestos for young women globally. However, the widely used term ‘Insta-poet’ is a misnomer to her. The 30-something-year-old literary sensation, who has 545,000 followers on Instagram, prefers being called a “pop poet,” as her words capture the emotional zeitgeist of our times from “Just Friends” to “Almost” (a verse about situationships). Still, there are critics who find her work superficial and self-indulgent (like how Plath was condemned for her self-serving confessional poetry), but Leav isn’t fazed and stands by her deliberate aberration.

Like Jo March, who has no qualms about subverting convention, Leav wants to march to the beat of her own drum. In one of her recent tweets on June 15, she said, “I don’t want to be in a relationship where I feel the constant need to explain myself. I don’t want to live in a world like that either.” Perhaps that’s her secret to success: wearing her heart on her sleeve, and not justifying or apologising for how she feels, which naturally leaves you coveting more.

High Net Worth: What was it like to be born in a refugee camp? And were there any important lessons that have shaped your work today?

Lang Leav: My life began in a refugee camp where my parents were seeking refuge from the Khmer Rouge regime. We emigrated to Australia where I grew up in the low socio-economic town of Cabramatta among people who had lost everything, including family members. Like many migrant children, I naturally assumed the role of translator for my parents. I learnt very early on to simplify the language and hone it down to the bare essentials. I understood the importance of clear communication from a young age, and I believe this has had a profound effect on my poetry. My writing style takes complex emotions and expresses them in a way that connects and resonates with my readers.

Out of your entire anthology of poetry, which one do you relate to the most and why?

My latest poetry book titled, September Love (out in November) is my most personal collection of poetry. In this book, I wrestle with themes of love, loss and identity, examining what it is to be a woman in the post-digital world, and ruminate on the various societal and cultural expectations that are placed on females. It is an ode to the life I have lived and all the ones that I didn’t.

Is there a dichotomy between you as an artist and you as a person?

The life of a writer is often romanticised in pop culture. The image of the brooding artist in a perpetual state of anguish jumps readily to mind. Many people who have met me on tour, tell me I am not what they imagined. I suppose they had pictured me as an extension of my work, dark and sullen, and instead found me to be the opposite. I firmly believe the measure of a writer is the work they produce. It has absolutely nothing to do with your lifestyle.

How would you differentiate your work from classic poets like William Blake and Yeats?

Stylistically, I have more in common with poets such as Sara Teasdale, Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson. Their poems are colloquial in tone, sometimes conversational. Like my influences, I often use rhyme and focus heavily on themes such as nature, love and time. There is a common misconception that poetry has to be difficult or esoteric in order to be valid. Which is simply not true. Shakespeare wrote ‘Pop Poetry’ for his time and was often ridiculed for it. Frost struggled to have his work recognised by the establishment and even Emily Dickinson had much of her poetry heavily edited.

What makes a piece of writing or a poem “good”?

Writing like any other form of creative endeavour is subjective. With the advent of social media, it seems everyone has an opinion on this, especially those who lack the necessary knowledge or insight to offer anything of value to the discussion. My latest novel, Poemsia, follows the story of a young poet named Verity Wolf. In this book, my protagonist finds fame and is consequently pitched into the crazy world of social media, where hate readers and pseudo-intellectuals will do anything to bring her down. Verity’s experience reflects the real world, where young, budding writers are immediately mocked for sharing their work. These bullies can do little damage to established authors like myself, but for someone starting out, it can be devastating.

Do you have advice for budding poets who hope to achieve fame and success?

This is the most common question I am asked when on tour and I suppose Poemsia was written as a kind of response. The book is filled with advice about the daunting world of publishing for anyone who wishes to follow in my footsteps. However, it’s a path you should only pursue for the right reasons. Writing is the last place you should look if your only goal is to achieve financial success. This applies to every artistic discipline. Most writers I know, including myself spent years, even decades working every day on their passion before they get their break. Fame and fortune should be an indirect consequence of writing, not the objective.

Famous literary couples such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre, Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir had a profound impact on each other’s lives. Since being in a relationship with Michael Faudet, how has he influenced your writing?

Relationships are often dismissed as frivolous yet the partner you choose to spend your life with determines so much. I met Michael when I was a starving artist and right from the beginning, he possessed this unwavering belief in me. I think it’s so important for any creative to have at least one person in your life who unequivocally supports what you do. Few artists make the leap to commercial success, and it’s been amazing to go through that experience, to see all my dreams come into fruition with my best friend at my side.

If you were not a writer, what would you be?

When I left school, I was given the choice between studying literature or art, and I chose the latter. I was passionate about both subjects, but at such a young age, you make these life-altering decisions on a whim. Since then, I have played the role of a multi-award-winning fashion designer and internationally exhibiting artist. It wasn’t until my poetry went viral that I focused solely on writing. But someday, I would love to wear the artist’s hat again.

What are you currently reading, listening to and doing?

I’m halfway through Picnic at Hanging Rock, an old Australian classic based on a true story. I loved it so much as a child, and it’s been a joy to rediscover it now as an adult. It’s made me nostalgic for other favourites such as Playing Beatie Bow, The Chocolate War, Hating Alison Ashley and The Green Wind. I’m listening to ‘Fetch the Bolt Cutters’ by Fiona Apple, and enjoying it immensely. Her voice as always is raw and evocative, whilst her lyrics have so much weight and dimension. Oh, and I’ve also started work on my third novel, which I’m really excited about!